Prima di parlare di atomi, occorre farsi un’idea di quali siano le loro dimensioni. E’ facile dire che il loro diametro medio si aggira intorno a qualche Angstrom. Ricordiamo che tale unità di misura vale 1/10000000000 di metro, o in alternativa 1/10000000 di millimetro. E’ più sorprendente affermare che il diametro di un capello (pochi centesimi di millimetro) può ospitare qualcosa dell’ordine di 100000 atomi affiancati (!). Una sferetta dello stesso diametro conterrebbe un milione di miliardi di atomi. Un milione di miliardi! Nel cuore di un atomo giace il nucleo. Questo ha le dimensioni di 1/100000 di Angstrom. Quindi occupa una porzione estremamente piccola dell’intero volume a disposizione. Il nucleo rappresenta la parte massiva. Se si potessero accatastare tutti i nuclei di un pezzo di materia si otterrebbe un piccolissimo volume superconcentrato avente massa analoga. Ammassando i nuclei di una sfera delle dimensioni di pochi centimetri (una palla da baseball ad esempio), si ricaverebbe una pallina di un diametro inferiore al micron. Praticamente invisibile ad occhio nudo. Quindi, i nuclei appartenenti a diversi atomi sono relativamente alquanto distanti fra loro. Nell’atomo ci sono anche gli elettroni. Si ritiene che abbiano dimensioni irrilevanti ed una massa decisamente inferiore a quella dei nuclei. Sorge a questo punto spontanea la domanda: se i costituenti di un atomo occupano uno spazio ridicolmente limitato, cosa c’è altrove?

Before talking about atoms, we need to get an idea of what their dimensions are. It is easy to say that their average diameter is around a few Angstroms. We remind that this unit of measure is 1/10,000,000,000 of a meter, or alternatively 1/10,000,000 of a millimeter. It is more surprising to state that the diameter of a hair (a few hundredths of a millimeter) can accommodate something of the order of 100,000 atoms side by side (!). A small sphere of the same diameter would contain a million billion atoms. One quadrillion! At the heart of an atom lies the nucleus. This is 1/100,000 of an Angstrom in size. Therefore it occupies an extremely small portion of the entire available volume. The nucleus represents the massive part. If all the nuclei of a piece of matter could be piled up, one would obtain a very small super concentrated volume having the same mass. By massing the nuclei of a sphere the size of a few centimeters (a baseball for example), a ball with a diameter of less than a micron would be obtained. Virtually invisible to the naked eye. Thus, the nuclei belonging to different atoms are relatively far apart. There are also electrons in the atom. It is believed that they have insignificant dimensions and a decidedly lower mass than that of the nuclei. At this point the question arises: if the constituents of an atom occupy a ridiculously limited space, what is there elsewhere?

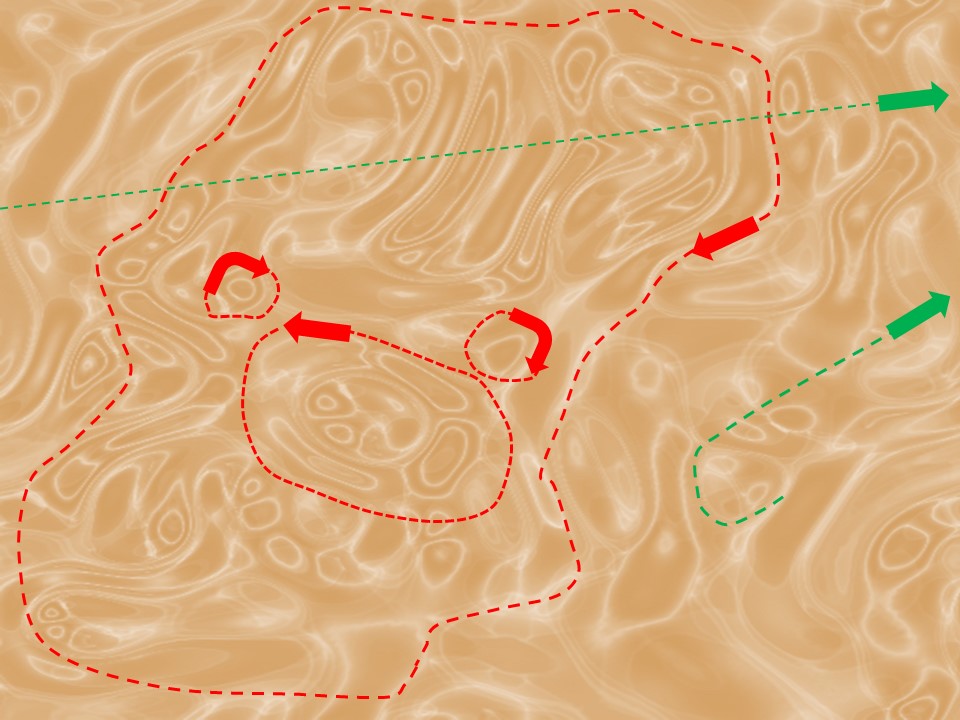

E’ nel contesto sopracitato che si sviluppa il lavoro di costruzione raccontato in queste pagine. E’ sì vero che una molecola contiene in gran parte del ‘vuoto’, ma è un vuoto di qualità: molta energia e, soprattutto, molta struttura. Non va dimenticato che le molecole, quando opportunamente sollecitate, emettono fotoni. E’ quindi importante prima di tutto stabilire cosa siano esattamente i fotoni (si veda QUI la nostra proposta), considerato che essi vengono molto citati sia nella teoria che nelle applicazioni, ma che non esistono definizioni formali se non la vaga asserzione che sono i ‘carrier‘ dell’informazione elettromagnetica. L’approccio quantistico è pertanto essenzialmente fenomenologico. Dal nostro punto di vista invece, una combinazione di particelle elementari (stabili o no) alimenta nel sottofondo elettromagnetico la creazione di complesse strutture, che possono assumere andamenti periodici con frequenze inversamente proporzionali alla loro estensione. Le geometrie hanno in prevalenza una topologia ad anello. Le forme possono sostenersi per tempi relativamente lunghi, o disperdersi nell’ambiente quasi immediatamente. Pseudo-carica e pseudo-massa si mescolano all’interno di tali agglomerati con densità che variano nello spazio e nel tempo. La figura qua sotto mostra una semplificazione bidimensionale di strutture dinamiche di diversa ampiezza, a gruppi contenute in altre. Le curve tratteggiate in rosso ne delimitano qualcuna. A causa di fattori esterni, la geometria può riconfigurarsi emettendo ad esempio fotoni (indicati in verde), i quali possono viaggiare per lunghi tragitti prima di essere riassorbiti da altre strutture.

It is in the aforementioned context that the construction work described in these pages develops. It is true that a molecule largely contains ‘vacuum’, but it is a quality void: a lot of energy and, above all, a lot of structure. It should not be forgotten that molecules, when suitably stimulated, emit photons. It is therefore important first of all to establish what exactly photons are (see HERE our proposal), considering that they are much cited both in theory and in applications, but that there are no formal definitions other than the vague assertion that they are the ‘carriers‘ of electromagnetic information. The quantum approach is therefore essentially phenomenological. From our point of view instead, a combination of elementary particles (stable or not) feeds the creation of complex structures within the electromagnetic background, which can take on periodic behaviors with frequencies inversely proportional to their extension. The geometries mainly display a ring topology. The forms can sustain themselves for relatively long times or disperse into the environment almost immediately. Pseudo-charge and pseudo-mass mix within these agglomerations with densities that vary in space and time. The figure below shows a two-dimensional simplification of dynamic structures of different amplitudes, contained one inside the other in groups. The curves dashed in red delimit some of them. Due to external factors, the geometry can reconfigure itself by emitting, for example, photons (indicated in green), which can travel for long distances before being reabsorbed by other structures.

In questo contesto, una molecola non è solo individuata dalla struttura propria dei nuclei atomici che la compongono, ma dal complesso sistema elettrodinamico che ne costituisce il suo ‘interno’ e che caratterizza il suo spettro. Gli elettroni svolgono solo una funzione stabilizzante. Si può trovare QUI una breve relazione riguardo alla struttura del carbonio. Le reazioni chimiche avvengono attraverso la rottura di strutture elettromagnetiche e la loro successiva differente riorganizzazione attorno ai nuclei coinvolti. Le regole sono quelle della dinamica dei fluidi (accoppiata all’elettromagnetismo) che si formalizzano in maniera più elementare attraverso le note regole stechiometriche. Le reazioni avvengono anche in base al comportamento generale del sottofondo elettromagnetico, che può essere alterato da variazioni di temperatura o dalla presenza di catalizzatori.

In this context, a molecule is not only identified by the structure of the atomic nuclei that compose it, but by the complex electrodynamic system that constitutes its ‘interior’ and that characterizes its spectrum. The electrons only contribute to stabilization. A brief report about the structure of carbon can be found HERE. Chemical reactions occur through the breaking of electromagnetic structures and their subsequent different reorganization around the nuclei involved. The rules are those of fluid dynamics (coupled to electromagnetism) which are formalized in a more elementary way through the known stoichiometric rules. The reactions also take place on the basis of the general behavior of the electromagnetic background, which can be altered by temperature variations or by the presence of catalysts.